We were thrilled to be invited to submit an essay to this brilliant collection – Rebalancing Rights – Communities, Corporations, and Nature.

What would change if we decided that the natural world we are part of had rights of its own – the right to exist, to habitat, to be free from pollution?

This collection began its life as an exploration of the concept of Rights of Nature. However, in early research and conversations it swiftly became clear that it would be worthwhile setting this concept into the broader context of the suppression of human rights and civil and political rights. As it was frequently pointed out, there is little point establishing a new set of rights if existing rights are not being honoured. Worse, given ongoing anti-environmental framing, it could set up a counterproductive contest, with the new rights for nature being portrayed as subjugating human rights even further.

Nicola Paris writes below – SUPPRESSION OF THE RIGHT TO PROTEST

Twenty-five years jail for peaceful protest. That is the potential outcome from the Espionage and Foreign Interference Bill (EFI) that was introduced by the Liberals and rubber stamped by Labor in 2018. It was slammed through with such speed that the cross-benches had one hour to examine what was described as the most serious overhaul to national security in 40 years.

Introduced alongside the Electoral Funding and Disclosure Reform Bill (EFDR) and the Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme Bill (FITS) it even troubled the Institute of Public Affairs, which called for the withdrawal of the legislation, stating “The IPA is inherently concerned about any proposal that seeks to ‘manage’ political debate by limiting freedom of speech.”[

Whilst these bills were pitched as managing emerging threats of foreign interference in elections and political decision-making, they are instead a Trojan Horse of breaches of civil liberties and human rights, wildly over the top and sloppily articulated, that had civil society up in arms. Amnesty International stated, “By joining regimes around the world in passing new, restrictive laws attempting to suffocate civil society under pretexts of “treason” and “security”, the opposition and government are lurching towards authoritarianism.”[

Whilst the work of the Hands Off Our Charities alliance was commendable and saw some of the seriously problematic aspects of the bills wound back, it was generally considered a lost cause to attempt to lobby the ALP to block the bills, or attempt much reform of the EFI legislation, in particular, given the lock step approach the Labor party has to voting in support of even the most destructive of policies relating to national security.

Consequently, legislation was passed that reframed “espionage” as working to act against “economic interests”, putting corporate dominance over civil and political rights into law. It was described by a range of NGO leaders as a “sick joke”, with GetUp’s Paul Oosting stating “Protesters who temporarily blockade a railway to an export coal mine could face 20 years behind bars for ‘sabotage’.” In this instance, sabotage is changed from an act of physical destruction to simply “limiting access to public infrastructure”—and not even critical infrastructure. This dramatic re-framing of national security legislation was only briefly highlighted in the tsunami of issues with the package of legislation.[ Despite concerned callers to ALP offices told the ALP had “fixed” the problematic aspects of the legislation, ironically this Act could see workers from ALP affiliated unions charged with terrorist offences should they engage in certain wildcat (unsanctioned) strikes.

This is just the latest in a pattern of legislation and practice at state and federal level that, when pieced together, makes up for quite the horror show: corporations prioritised, civil liberties tossed, dissent criminalised, hard-fought human rights relegated to paper promises, a surveillance state growing, and government architecture built by both Labor and Liberal governments that is incredibly dangerous, and yet to be deployed in full force.

Peaceful protest has been instrumental in battles for workers’ rights, stopping the Jabiluka uranium mine near Kakadu, stopping the mighty Franklin River from being dammed, for Aboriginal people and women having rights to vote, for forests we enjoy now as national parks, for areas of country that are now protected from fracking and unconventional gas, and so much more.

With the de-funding of critical support services, increasing regulation and administrative time required, and broad-reaching attacks on charities, non-profits, legal and support services, we are seeing the successful de-fanging of organisations that should be resourcing and leading a powerful pushback. Some of the large environmental NGO’s are so timid in their approach to supporting civil resistance they will rarely even share content or reports from the frontlines. Activists at the grassroots are facing increasing penalties, hostile magistrates, bureaucratic red tape over “designated protest zones”, and a student movement that has been thinned by the huge stressors in their lives—too busy trying to cover rent and food, working and studying with precious few hours for civic engagement.

This paper examines some of the challenges to protest in Australia, from being branded as terrorists to increased penalties, violence and intimidation to surveillance and infiltration.

Protest as terrorism

As Rebecca Ananian-Welsh and George Williams outline:

Prior to 9/11 Australia had no national laws dealing specifically with terrorism. Since then, the Australian government has enacted more than 60 such laws, an approach Kent Roach aptly described as one of ‘hyper-legislation’. Australia’s national anti-terror laws are striking not just in their volume, but also in their scope. They include provisions for warrantless searches, the banning of organisations, preventive detention, and the secret detention and interrogation of non-suspect citizens by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (‘ASIO’). The passage of these laws was eased by Australia’s lack of a national bill or charter of rights.

None of the significant changes to terrorism and security legislation introduced post 9/11 have been overturned. They must be seen as an increasing risk to peaceful protest.

Conservative commentators are aware of the power of framing peaceful protest and civil disobedience as terrorism, and this rhetoric is used to marginalise and scare people away from being involved. This is particularly jarring for people in regional areas. Caring for climate and country has been weaponised and politicised in this way. Anyone can be tarred with this brush; simply having opinions that don’t support mining development can be enough, according to Queensland MP, George Christensen: “The eco-terrorists butchered the international tourism market for our greatest tourism attraction, not for the reef but for political ideology”.

In contrast, a handout from the government’s own National Security website states, “a terrorist act does not cover engaging in advocacy, protest, dissent or industrial action where a person does not have the intention to urge force or violence or cause harm to others.”[

In the full report from his 2016 visit, United Nations Special Rapporteur for Human Rights, Michel Forst, was scathing of these rhetorical attacks (as well as other legislative attacks):

I was astounded to observe what has become frequent public vilification of rights defenders by senior government officials, in a seeming attempt to discredit, intimidate and discourage them from their legitimate work. The media and business actors have contributed to stigmatization. Environmentalists, trade unionists, whistle-blowers and individuals like doctors, teachers, and lawyers protecting the rights of refugees have borne the brunt of the verbal attacks.

The oft-repeated phrase “professional protestors” touted by conservatives gives a view into their thinking. It is anathema for them to consider why people might act in the greater good. It confuses them. Yet, despite the cheques from George Soros continuing not to turn up, everyday people in their tens of thousands are resisting the agenda that is set for us, despite the challenges set out in this paper.

Increasing penalties for civil disobedience

There has been an escalation in protest relating to climate change and coal infrastructure in recent years, with increasing numbers of “ordinary” people taking extraordinary action and placing themselves in the way of the fossil fuel industry. Although ultimately unsuccessful, the campaign to stop the expansion of Whitehaven coal in New South Wales created a “new normal” in terms of civil resistance to new coal projects, with more than 300 people arrested in an attempt to block coal expansion and clearing of important habitat for at risk species.]

Over this period, we have seen increasing penalties and numerous new pieces of legislation designed to deter protest. In NSW, 2016 legislation increased penalties for certain protests up to a maximum penalty a seven-year jail term. In addition, the recently introduced Crown Land Management Regulation Act creates new powers to disperse protests, including the ability for public officials to “direct a person” to stop “taking part in any gathering, meeting or assembly”.[

Even without legislative change, penalties are being increased. In 2018 a group that trespassed and entered the Adani owned coal export facility were collectively charged $72,000. The group included a veteran, young students and a single mum. Many of them were first time offenders. They locked themselves to a conveyer belt and disturbed the operation of the port facility, interrupting coal exports for a number of hours. Whilst it was a dramatic protest, it was done with safety in mind, and is hardly a new tactic. Multiple similar actions have occurred over the last ten years at Newcastle and other NSW coal port facilities, elsewhere in Queensland and at the very same facility at Abbott Point.

For comparison, in 2010, a Greenpeace team occupied the Abbott Point terminal, also delaying export facilities. This included fifteen activists, twenty-three charges and resulted in fines totalling $6000.[ The total is less than one single charge of $8000 handed out to first offenders last year.

The subsequent publicity saw an offer of pro bono legal assistance for appeal by Queensland-based barristers and a community legal service. In March 2019 the welcome news was received that the penalties were mainly cut by 75%—dropped down to between $2000 and $3000—in what can only be seen as a significant rebuke to the original sentence. Even these reduced fines still appear stark compared to the penalty Adani received for polluting the Caley Valley Wetlands adjacent to their facility—a mere $12,000— which they are still challenging, with another discharge reported in early February 2019.

Similarly high charges were often seen during the long running campaign at the Whitehaven coal expansion near Maules Creek, as well as nearby where people were challenging unconventional gas operations in the Pilliga forest. Local magistrates had given a series of very high penalties, which were overturned and significantly reduced when challenged.[

Penalties for non-violent direct actions that result in arrest can vary significantly, depending on the magistrate, the political context and surrounding circumstances. A volunteer legal group that supports people taking direct action on coal and climate concerns has been recording outcomes, and noting patterns of higher penalties for similar offences when handed down in Central Queensland In Queensland it is very rare for people to receive a recorded conviction for low level non-violent protest, but the fines are incredibly varied, and seem to increase as people travel north, apparently breaching the legal concept of parity—that people doing similar things in similar circumstances should be treated relatively evenly.

In 2018, one young woman involved in an action stopping a coal train on a railway received a $200 fine while another person arrested on the same charge received a $2400 fine.[ Both were first time defendants with clean records. The main difference? One magistrate was based in Brisbane and the other based in Bowen—the town nearest to where actions have taken place on Adani rail infrastructure. Bowen locals have been part of a strong opposition to anyone challenging the Adani project. In this politically charged environment, even people involved peripherally with anti-coal activists can be targeted. In 2017, a local small business owner was contacted and berated by the police, the local Mayor and the local state Member of Parliament and had multiple visits from council, all for the simple act of accepting business from peaceful protectors who were visiting Bowen.

In what appears to be an escalation in sanctions against specifically at frontline climate activists, at an event in Newcastle in 2018, two senior citizens, including Bill Ryan, 96 year old Kokoda veteran and numerous other activists were charged with “armed with intent”—in relation to the possession of “lock on devices”, others with “aiding and abetting” simply for filming on public land—charges the police directly admitted they were “trying on”. Also, in Melbourne in early 2019 a number of houses were raided, computers and phones seized and people received rare riot related charges—some months after a relatively innocuous office occupation at BHP, which had followed a well-worn path and saw no charges laid on the day.

The uneven application of the law applies even more blatantly to Indigenous people, who are more likely to be jailed for non-violent offences, and face a significant chance of death or injury in custody.[ With levels of incarceration at shameful levels, the risk for Aboriginal people in participating in peaceful protest is markedly higher. Simply being black and mildly angry in public can risk police attention.

At the Commonwealth games in 2018, Aboriginal people from many different nations gathered in resistance as they had previously for “Stolenwealth games”. They negotiated with police in good faith regarding a sanctioned camp site. They were misled about bail conditions, had bright lights shone into their camp and overt surveillance, some would argue, to the point of harassment. A number of activists were seemingly targeted for arrest, with tactics that were misleading. There has also been a pattern of increasingly obstructive policing tactics in Melbourne where, in 2018, the police attempted to block a massive march organised by Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance at the Flinders Street intersection, and this year refused to let the authorised vehicle accompany the protest march in its final stages,[ thereby endangering the massive crowd who were unable to hear updates and instructions from organisers.

The constant over-policing of Aboriginal protest events is a pattern that has been noted by Melbourne Activist Legal Support and repeats all over the country. Not only can this be traumatic for Aboriginal people, who are many times more likely to have had a negative experience of police, it serves to imply that they are dangerous and in need of policing, thus attempting to deter mainstream participation in their protests.

Violence and intimidation tactics

Whilst people engaging in civil disobedience sometimes can expect to be arrested in certain situations, they should not be assaulted in doing so.

People who engage in civil disobedience are very often painted as deserving of violence, surveillance or harassment. Some people who otherwise would not consider it reasonable to assault people in the street seem to think that if people are committing acts of civil disobedience, that they are somehow “asking for it” and a bit of “roughing up” is to be expected.

It shouldn’t be expected, it shouldn’t be normalised, and assault is against the law, even if you are wearing a uniform. That doesn’t stop it happening. And it doesn’t stop it happening more to Aboriginal people, who may have committed no offence at all.

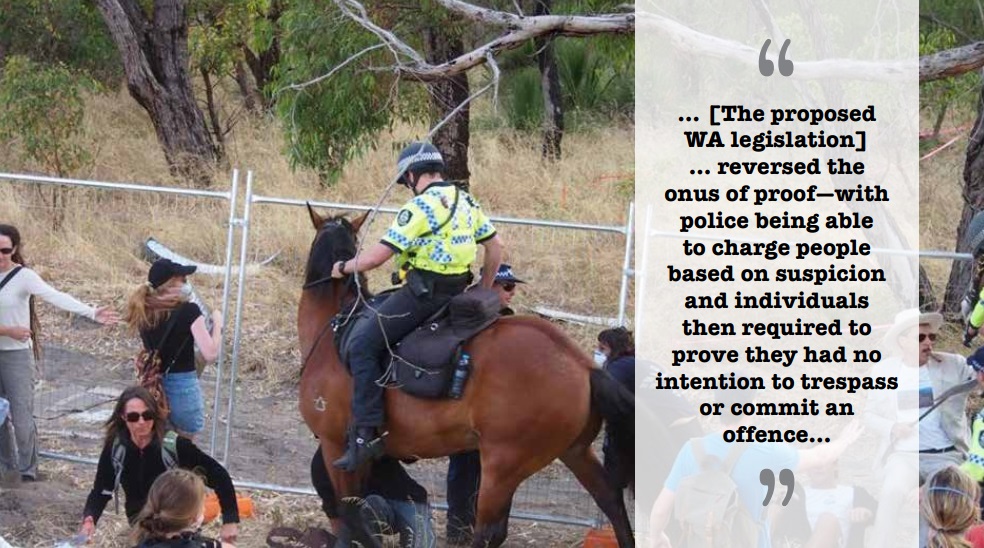

In early 2017, a campaign to save the Beeliar wetlands in Perth, Western Australia was subject to appalling tactics from police. In a community survey undertaken with more than one hundred respondents involved in the protests, the community trust in police was significantly eroded across the board. Of the more than two hundred people that were arrested, the vast majority of them had never been involved in peaceful protest, with a significant number never even having participated in sanctioned rallies.

And it was a rude awakening for these “mum and dad” protestors, as they saw their precious local natural places bulldozed and destroyed. One participant told me: “As a Coolbellup resident, I feel like my relation to the police has fundamentally changed. While police were lining our streets to allow bulldozers to destroy our urban bush there was a distinct lack of engagement with locals and their concerns.”

The complaints included people who were trampled by horses, strip searched without reason, assaulted, threatened with pepper spray and tasers. The police commissioner completely dismissed the notion of any type of independent inquiry, despite comprehensive evidence gathered, insisting instead that individual police complaints be made. Given that making individual police complaints had resulted in additional charges for numerous people, it is understandable there was some hesitancy to take this option. WA suffers from the same systemic problem with policing complaints across the country—police investigate police. It is no wonder that action on inappropriate behaviour is rarely taken, nor are police being seriously disciplined.

Numerous assaults were documented at the Sydney Westconnex road protests, and similarly in the East West tunnel protests in Melbourne, where women repeatedly reported patterns of being grabbed by the breasts and targeted by male cops. The Occupy protests in 2012 documented over 80 injuries. These are just a handful of examples.

And then there is the low level ongoing harassment: constantly being pulled over by police; searches on spurious grounds; random breath test road blocks somehow regularly appearing near protest sites where they have rarely, if ever appeared before; the use of police powers to target well-known local protestor vehicles with infringement notices, finding such outrageously dangerous instances as a loose clamp on a battery, or a single thread loose on a seatbelt, to ensure that the cars are considered unroadworthy, and subject the owners to the expense and time of having to rectify non-issues. Roadblocks have been put in place in the lead up to major events, such as the gathering known as “Lizards Revenge”, a “protestival” against uranium mining in South Australia, where a proposed police roadblock meant a 12-hour alternative route would need to be traversed to gain access to the encampment.

At the other end of the spectrum, increasingly militarised state police forces, using high impact pepper spray balls,[ tasers and rubber bullets, add to the threat facing protesters. Police are increasingly indistinguishable from storm troopers in their body armour, or patrolling Parliament House with machine guns. Riot police are now used as quasi corporate mercenaries, coming into regional towns to escort the gas companies onto country against community wishes.

Being labelled as terrorists, being followed by police, being violently arrested, strip searched and receiving huge penalties are factors that are designed to deter civic action in defending our natural places. And yet we are seeing brave people step up in ever greater numbers.

Right to protest vs right to profit

Whilst protesters have long been penalised for getting in the way of business, there has been a growing trend of legislation that is specifically written to prioritise business interests over that of individuals. However, if big corporations do damage to the environment, they are subject to paltry fines and penalties. Like the previously mentioned minor fine to Adani, Santos Limited was fined $1500 in March 2014 by the Environment Protection Agency after a leak which resulted in increased levels of lead, aluminium and arsenic, being found in the aquifer, as well as uranium at 20 times the safe drinking water guidelines. Eastern Star Gas was fined $3000 for discharging polluted water into Bohena Creek in the Pilliga, in North West NSW. Meanwhile community members who peacefully resisted the expansion of unconventional gas projects were fined up to $6000.

Jonathan Moylan was the first climate activist in Australia to face the very real possibility of a jail term for daring to touch the market. Having written a hoax press release, ostensibly from the ANZ bank, announcing them pulling out of the contentious Whitehaven coal project,[ he was charged under ASIC legislation that is intended for corporate fraud. Whilst it is difficult to determine what factors went into the judge’s non-custodial sentence, the solidarity campaign was large scale, with support pouring out across the nation and internationally.

Southern Cross University Lecturer Aiden Rickets talks about the suite of new legislation in NSW introduced in 2016: “There’s a tenfold increase in the fine for trespass (from $550 to $5500) but only if it’s a business premises, such as a mine. This is a continuation of the approach taken in WA, and Tasmania where the newly invented ‘right to do business’ is given precedence over recognised civil and political rights.”[

In Tasmania the fractious relationship between forest activists and the logging industry has been going on for decades now, and the politics remain fraught. In 2016, the ‘Workplaces (Protection from Protesters) Act’ was introduced, with a particular focus on penalising interruptions to business. Hannah Ryan & Emily Howie write that:

The government argued that it needed to protect businesses operating in Tasmania’s forests from the inconvenience visited on them by protesters. Importantly, the laws did not only target protesters—they only applied to protesters. The restrictions on movement the law provided for applied only to people engaged in any activity that promoted “awareness of or support for … an opinion, or belief, in respect of a political, environmental, social, cultural or economic issue” taking place on business premises.[

The laws had maximum penalties of ten thousand dollars and five years jail and were deemed unconstitutional in October 2017 in a landmark ruling in a case brought by Bob Brown, with a finding that they interfered with the implied right of political communication. At the time of writing, the Tasmanian Liberal government is seeking to reintroduce an adapted bill, with Building and Construction Minister Sarah Courtney stating that “protection of the rights of Tasmanian businesses and their workers to earn a living free from disruption is one step closer.”

In WA in 2015, there was legislation due to be introduced which was admirably kept at bay by the Peaceful Protest Alliance—a diverse grouping of farmers, conservationists, unionists and the legal fraternity.[ The law would have made it an offence to physically block a lawful activity and to make or possess any device intended to be used to carry out that offence. It also reversed the onus of proof—with police being able to charge people based on suspicion and individuals then required to prove they had no intention to trespass or commit an offence. The strong community opposition saw this languish at the bottom of the government’s agenda for months, and then be abandoned as the ALP came into government.

Surveillance and infiltration

One of the more insidious impacts is subjecting community organisation to surveillance with all the incredible sophistication of the tools currently available to a range of government agencies such as ASIO, ASIS and others. For example, the National Open Source Information Centre sign up to email lists and Facebook pages to monitor the public-facing events of “Issue Motivated Groups”, as state police refer to environmentalists or animal rights activists. Then there is the collusion between government and corporations such as Google and Facebook, or the surveillance agreements and the 5 eyes program, where governments mutually agree to spy on each other domestically to avoid pesky laws about monitoring their own citizens who aren’t suspected of crimes.

The Leard blockade, established in response to the expansion of the Whitehaven coal project in regional NSW, was subject to a large-scale infiltration, with at least six different people identified by activists as undercover corporate operatives.[ Some activists involved theorise that there may have been collusion with police in relation to some actions being exposed and de-railed, and this is certainly a pattern that has been seen overseas.

The concepts of inclusion and acceptance of people in grassroots radical politics can work to the detriment of groups by enabling infiltration. People who may not “fit in” in other places can be welcomed with open arms by activist groups with ideals of living in a more inclusive community. This was one reason why some of the more unusual suspects involved in the Leard blockade infiltration were not outed sooner. It is a cost that often people are willing to bear, but the most destructive aspect of infiltration is the distrust and paranoia that it leaves in its wake, in this case doing serious damage to group dynamics, and impacting on the mental health of activists.

This is not an isolated incident—police have been outed in other groups, and another public disclosure was made in 2008 when activists involved in animal rights and peace protest groups discovered undercover police in their midst. Even this is just scraping the surface. Not only has the government made it legal to essentially spy on the activities of millions of Australians with metadata laws, with some sixty agencies or more allowed access,[ but we can only theorise about the level of digital intrusion, infiltration and surveillance that remains uncovered.

Thankfully we do not seem to have seen the level of infiltration as seen in the United Kingdom which saw lives ruined as police conducted long term relationships with multiple women, in one case even fathering a child with an activist. There has been excellent resistance work in the UK to hold these people to account.[

Dissent = Democracy

Terania Creek in NSW was the site of the first forest blockade in the world. Members of that protest group were recently awarded community recognition of their service to the environment, and the Premier of the time, Neville Wran, noted the subsequent legislation that protected the northern rainforests as his proudest achievement. In a letter in support of the protesters, Wran wrote:

Terania Creek and the men and women who fought for it, played a critical role in shaping my views and the views of the Government of the day in relation to conservation. Indeed, there is no doubt that Terania Creek was a milestone in the history of conservation in Australia.

Peaceful protest and civil disobedience are vital and legitimate tools in creating positive social change. Contrary to conservative rhetoric, they are broadly supported across Australian society. The right to strike is being vigorously defended by ACTU head Sally McManus who has resonated across the country with union audiences ardently supporting her bold positioning. Internal polling of key members in leading activist organisations has indicated a high level of support for strategic civil disobedience; international NGO, Avaaz recorded historically high support for civil disobedience in member surveys; and the Australia Institute polled high levels of support for protection of farmland and water systems using these tactics.

Despite the various challenges to peaceful protest outlined here, the majority in this country still have the privilege of being able to participate in civil disobedience with relatively little impact on their lives, unlikely to be killed in a jail cell or while protesting. This is a privilege to be used before it is taken away. And it is worth it, not only for achieving its direct goals, but also for the sense of community that it builds, the lifelong friendships, the bonds between mob and whitefullas working together, the resilience and practical skills that are learned, all factors that will be vital for moving forward in a climate changed world.

We are already seeing the stirrings of new waves of activity—record breaking turn outs for Invasion Day bringing city streets to a standstill, tens of thousands of students “striking for climate”, the rapid growth of Extinction Rebellion,[ #MeToo and movements against gendered violence, and Indigenous communities rising up world-wide.

Peaceful, bold protest and civil disobedience is critical to balance the scales. The only way they will tip is if more people stand up to support those on the frontlines—getting involved, sharing stories, calling on NGOs to step up, funding grassroots movements and capacity building, supporting Indigenous led resistance, or doing the slow and necessary community building work. If more people actually put their weight on those scales, we can start to tip the balance.

The greatest challenge we face is people not believing they have power, because together we do.

Cross references, footnotes and the entire series can be downloaded here.